By Renée Tillotson

It’s no big secret that my husband, Cliff, has been my hero ever since the first weekend I met him in 1975. He was both so kind to me as a novice skier and so brave as an expert skier himself – launching himself off a super high precipice, landing, and effortlessly skiing down the steep slope below – that my heart still flutters at the memory.

Since that time, I’ve become a huge champion for protecting the health and safety of our bodies.

When I met Cliff, I was a competitive gymnast in college, never doubting that it was just fine to keep spraining my wrists and ankles repeatedly. But I’ve been moving in the “listen to your body” direction ever since I started doing Nia in 2002.

By the time I opened Still & Moving Center in 2011, I had become a “let’s protect our bodies” cheerleader. In 2021 I launched the Academy of Mindful Movement to train coaches and instructors from all kinds of sports, fitness practices, performance arts, and therapeutic movement modalities. Our first goal as movement teachers is to KEEP THE BODY SAFE. Like a doctor taking the Hippocratic Oath, we at least pledge “to do no harm” in coaching our students.

Cliff has never held listening to his body as a huge priority during his various athletic or work endeavors. I often have to let him know when he has blood dripping off his arm or leg or forehead… Maybe some tool jabbed him or he scraped himself loading his outrigger canoe onto the top of his truck – he didn’t notice. He’s a little better about using sunscreen after some skin cancer issues, but I still need to remind him to use aloe when he comes in bright red after hours in the sun – working, fishing, racing, golfing, whatever.

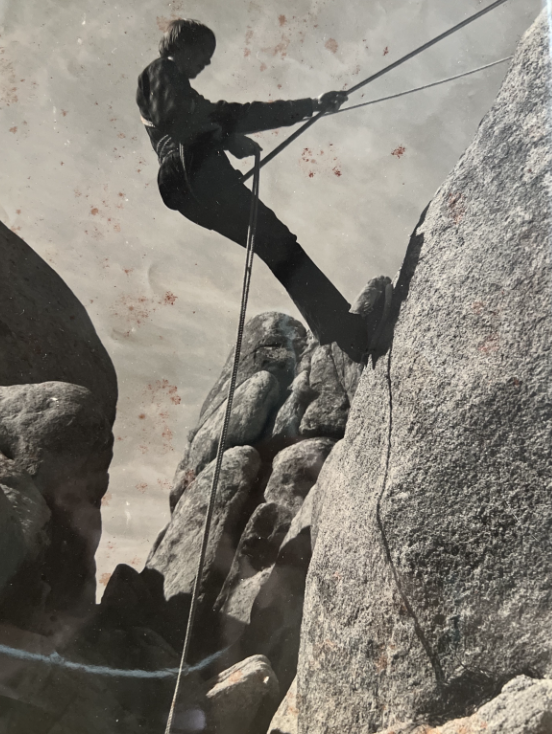

Since his preteen years, this Cliff of mine has been rock climbing (funny name coincidence, right?) In our early thirties, Cliff scaled the 3,000-foot rock face of El Captain in Yosemite National Park. We’re talking scary stuff. Each night, he was literally “hanging out” thousands of feet off the ground in a rock climber’s hammock, dangling from hooks in tiny crevices in the rock. On one such climb, Cliff fell and broke his wrist. Not wanting his wife (that would be me) to know and worry that he had hurt himself on the rocks, Cliff came home and never said a word about his fall. He went straight back to his landscaping job, digging holes and trenches, carting wheelbarrows of heavy stuff around, all WITHOUT a cast or brace on his wrist. 😫

Did that fall stop his extreme rock climbing? No.

On the third day of an ascent up El Capitan, on a particularly treacherous part of the climbing route, Cliff’s hands peeled off the rock. He plummeted downwards, dozens of feet. Finally, the rope he was attached to caught him. Banging against the granite rock face on his way down, though, Cliff broke at least one rib. He still bears the mark of that brush with death: one of his ribs pokes out at a crooked angle beneath his skin. Of course, I only learned about these misadventures years later, after we had moved to Hawaii, where there are no great rock faces to climb.In his fifties, Cliff finally received another huge lesson about the critical nature of body listening when he was at the apex of his Hawaiian canoe-paddling regimen. Here he was, a ha’ole man from California, racing on the very successful Kailua Canoe Club team of very local guys.

The team started each rigorous practice by lifting their huge, 400+ pound six-man canoe into the surf. As Cliff climbed into his assigned front seat for one of their practices, he set out once again to prove himself a worthy team member.

Let me interrupt this part of the story to remind you that our human musculature is strong enough to do damage to various parts of the body if we’re not careful. Cliff is lanky, yet surprisingly strong.

There he sat in that front seat with his feet pressed against the inside hull of the canoe. To get the most powerful stroke he could muster, he shoved with all his might into his feet. He hinged at his waist to lean forward with his paddle, digging into the water in front of him. Then he leaned back, forcefully pulling the paddle backwards to one side of the canoe.

That’s when he heard an ominous popping sound and felt a shooting pain through his back. The strength of his own pull had seriously injured two of his vertebrae.

If I had been there and knew what had just happened, you can imagine me, hands to my head, shrieking at him “Get out of the boat, dude! Now!”

But did Cliff say a word to his teammates or his coach? No. Did he ask to get out of the canoe? No. He just “manned up” and swallowed the pain until the end of practice. Typical.

Ai yai yai. This kind of treatment of the body drives me crazy. Poor body! It works so hard for us and does anything we ask it to do for us, as best as it possibly can. It’s just like a devoted dog who ran the pads of his paws off to keep up with his human friend on a long run. The poor, innocent body is just like that dog, trying its best to please us and do what we want.

The result of Cliff’s Superman efforts in the canoe that day, ignoring all body signals to the contrary? Two lower back discs that were not just “herniated”, they were “extruded”. After weeks then months of mind-numbing pain, he finally found an excellent back surgeon who solved the problem as well as is possible in such circumstances.

Cliff will never have his healthy, uninjured spine again, but he has eventually been able to return to most of his past activities – with a great deal more respect for the idea of listening to his body. He stretches first, and occasionally acknowledges that a 67 year-old-body cannot do some of the things it used to do. Ya think?!?

Did he stop his uber-athletics altogether? Although he stopped running the Honolulu Marathon a couple of years ago, he continues solo canoe paddling, TRYING to be mindful about it.

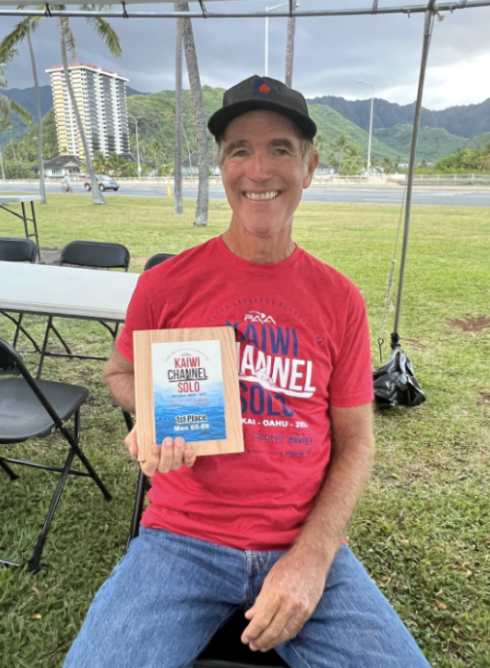

In 2023 he was the only person in his age category to complete the grand finale competition of the season: the 32-mile solo outrigger crossing from Molokai island to O’ahu across the Ka’iwi Channel. He was exhausted, yet uninjured. You can read about that here.

He’s been training and competing since December for the 2024 Molokai Solo this May. The most grueling lead-up competition each year consists of three races in one weekend in March. To prepare for the upcoming Molokai Solo, Cliff did the sprint and the mid-distance races on a Saturday. He did fine.

The next day, weather and ocean conditions for Sunday’s race turned out to be… Well, let’s just say that if I had known what a storm was brewing out there on the sea before Cliff left the house, I probably would have laid down in front of his truck to prevent him from driving off to the race.

However, I was blissfully unaware of the conditions… until Cliff returned home late that afternoon. The seas had been RAGING as he and his fellow racers left Makapu’u, heading toward the finish line at Magic Island, a beach near Still & Moving Center. Many times that day, Cliff in his skinny outrigger was plunging down 20’ tall wave faces, just hoping his canoe wouldn’t break in half when he reached the bottom of the wave trough. It didn’t. Fortunately.

At one point that afternoon, Cliff saw the gray sea in front of him suddenly turn black. What the heck?!? Before he knew it, two adult humpback whales rose up in front of him, maybe 40-50 feet long each. “Wow!” I innocently and ignorantly exclaimed that evening when he was telling me the tale of his race day. “Wasn’t that exciting!” (Yes, I confess that I am still a total sucker for Cliff’s adventure stories.) Cliff looked me squarely in the eye and replied, “No. It was terrifying. Those whales were huge and really close. They could have sunk me.”

Oh.

Surviving the close call with the humpbacks, Cliff fought on through the waves and weather. But by the time he reached Kaimana Beach at the beginning of Waikiki, he was physically and psychologically drained. He was 95% of the way to the finish line, but his body battery was empty. And he knew it.

Then my hero did the most heroic thing of all. He stopped.

He waved down one of the race’s safety boats to pick him up, handed up his canoe to the motorboat driver, and treaded water while the driver wrestled to tie the canoe down to the boat in the fierce winds that continued to howl across the waves.

As it turns out, though, Cliff’s adventure held one more nail-biting incident. As he floated on his back in exhaustion, the safety boat drifted farther and farther away from him while the driver still struggled to secure the canoe. Cliff was alone on a big ocean. He then heard a roaring sound getting closer. And closer. Righting himself in the water to see what was coming, Cliff saw a gigantic sailboat bearing straight down upon him.

The roaring sound came from the sailboat captain’s desperate effort to make a 90-degree turn to avoid plowing under the human being unexpectedly bobbing in the rough seas in front of him. He did make the turn. Fortunately.

I am so glad I wasn’t there to see this whole harrowing experience unfold. Just hearing about that race put an extra year of wrinkles onto this fair face of mine. Hah!

Why, you might ask, do I consider all these daring outdoor adventures to be the stuff of heroes? Good question. If it were just a matter of seeking personal glory and adulation, that would simply be an ego trip. In Cliff’s case, he just tosses all his medals and trophy plaques onto a shelf in the closet and never talks about them. Yet he’s always steeling himself – physically, mentally, emotionally – for any challenges that may come his way. He’s always on the alert for people in danger or in need and has come to the rescue in many circumstances. To me, he truly qualifies as a hero.

Of all the brave things Cliff has done since this last year, the one I most appreciate is his quitting that race. Although he DQ’d (Dis-Qualified) himself from that death-defying race, the Cliff took care of my husband while he remained alive and unbroken. Yay! I may need to award him an honorary diploma from the Academy of Mindful Movement… for quitting!

Renée Tillotson

Renée Tillotson, Director, founded Still & Moving Center to share mindful movement arts from around the globe. Her inspiration comes from the Joy and moving meditation she experiences in the practice of Nia, and from the lifelong learning she’s gained at the Institute of World Culture in Santa Barbara, California. Engaged in a life-long spiritual quest, Renée assembles the Still & Moving Center Almanac each year, filled with inspirational quotes by everyone from the Dalai Lama to Dolly Parton. Still & Moving Center aspires to serve the community, support the Earth and its creatures, and always be filled with laughter and friendship!

Get the Still & Moving App

This post is also available in: English (英語)