By Renée Tillotson

If you were writing your Ode to Joy, how would it sound? And how would you achieve it?

As we look into a new year, a new decade, with the theme of Deep Joy at Still & Moving Center, I’m wondering what it is that brings this sense of Joy. It’s not the kind of joy whose opposite it sorrow. This Deep Joy often finds its way through a world of suffering and sorrow, to emerge, radiant, connected to everyone and everything. Kahlil Gibran reminds us that the deeper sorrow carves into our being, the more room we have for Joy.

Actually, I suspect that we truly find this Deep Joy to the extent that we feel our life has purpose, meaning. When what we do affects others – hopefully positively – our existence here on earth has made a difference. It takes some people a long time to find their specific mission, and in the meantime, everything we do can be a preparation for it. Sometimes it just falls into our lap, after a long period of yearning and waiting. I didn’t know I was meant to open Still & Moving Center until 7 months before we opened, and I was 55 at the time.

I can’t tell you how much Joy it’s given me since then to hold space for our students, teachers, therapists and staff to “claim their magnificence” in this community center / school of moving meditation! I certainly could never have accomplished it any earlier in my life, as my work, study, family, professional experience, and spiritual practice all formed necessary foundational stones.

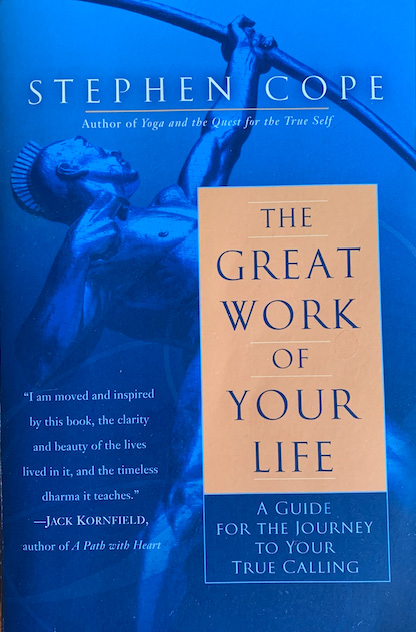

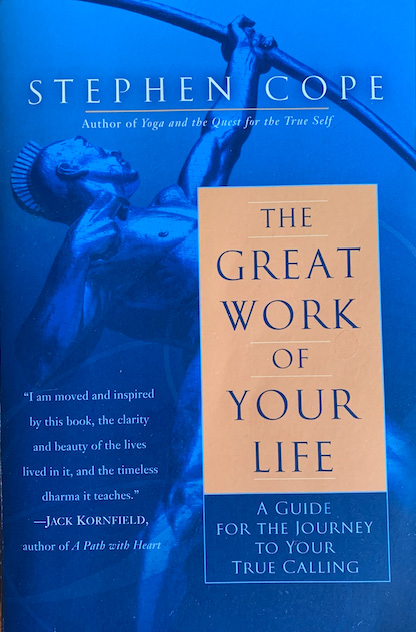

The book I’m reading now, The Great Work of Your Life: A Guide for the Journey to Your True Calling by Stephen Cope, is all about finding and pursuing our dharma, a richly conceptual Sanskrit word meaning our life-purpose, duty, raison d’être. The underlying assumption is that each of us comes into the world with a unique purpose to fulfil. If we look at our circumstances and at the many attributes of our natures, we can find what it is we are best suited to do in this life. It may or may not be how we earn our living, financially speaking. It always has to do with how we find the soul-satisfaction of finding and doing what we do best.

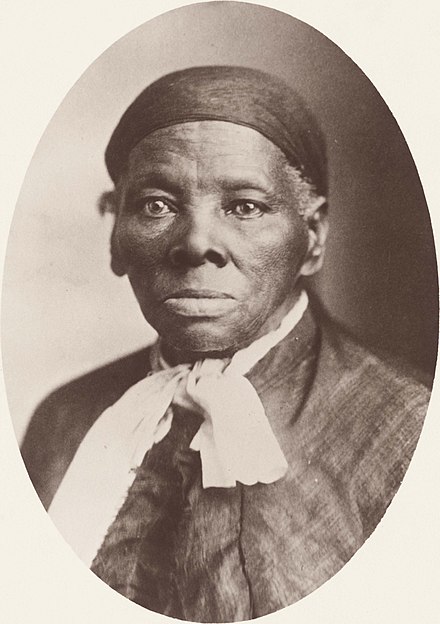

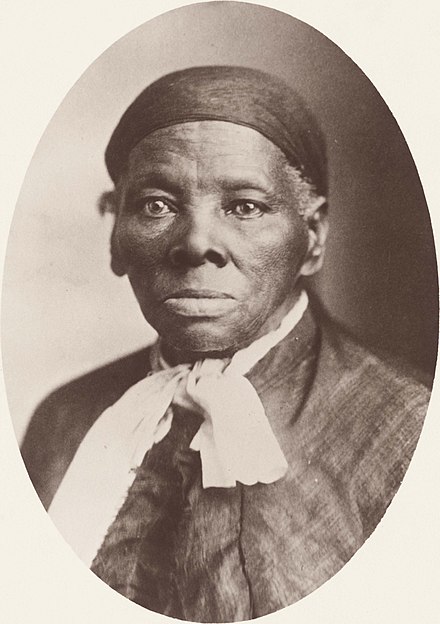

I love the author’s real-life examples, such as Harriet Tubman, a black slave who had watched her family members being split and sold to other plantations. After escaping herself, Harriet helped thousands of others to freedom via the “Underground Railroad” of which she was a “conductor”. She performed these services at great personal risk. She was a highly WANTED person by Southern plantation owners whose slaves she was spiriting away. They wanted her re-enslaved or dead. While she could have stayed safely in the North, Harriet felt absolutely compelled to return to the South again and again to rescue others, regardless of possible consequences.

Harriet showed an uncanny ability to avoid capture, to change plans in a twinkling based on an intuition that told her to do so. As a Christian, she always felt as if she was guided and protected by Providence. She asked for no payment for her services, and even after the Civil War and Emancipation of the slaves, she lived the most modest of lives in meager circumstances. Doing our dharma doesn’t always yield a pay check. I imagine her satisfaction, her Joy, at realizing how many people she had saved from cruelty and led to freedom, how many families she had reunited.

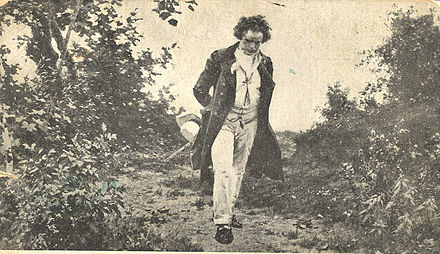

Ludwig van Beethoven’s fulfilling of his life purpose led him through tremendous suffering in other ways. He was born to a musical family, receiving his early musical training from his father, a talented but hard-hearted man. Ludwig developed such an eccentric personality, it was difficult to spend time with him. No one else at the time could completely comprehend the new rhythmic and melodic structures he was creating. Yet his dedication to his work and his genius as a musician, composer and conductor dazzled all the society people of his day.

To his horror, Beethoven began losing his hearing while still in his twenties. He first tried to hide it from people, then went into seclusion. Being thwarted in the occupation he so brilliantly performed, he questioned his existence, came close to losing his mind, and contemplated suicide. Yet he kept hearing the music in his head, in his soul. Beethoven held onto his musical dharma for dear life – literally – when all else failed him, and went on to compose his greatest masterpieces after becoming deaf. He came to realize that the world needed his music. Only by bringing forth the music moving within him did Beethoven find a sense of peace, even Joy.

Indeed, he composed his final complete symphony, Beethoven’s 9th, based on Schiller’s poem “Ode to Joy”. Its debut performance in 1824 happened less than three years before his death at age 56. Violinist Joseph Böhm recalled the performance:

“Beethoven himself conducted, that is, he stood in front of a conductor’s stand and threw himself back and forth like a madman. At one moment he stretched to his full height, at the next he crouched down to the floor, he flailed about with his hands and feet as though he wanted to play all the instruments and sing all the chorus parts. — The actual direction was in [Louis] Duport’s hands; we musicians followed his baton only.”

Beethoven was several measures off and still ‘conducting’ when the musicians finished the piece and the audience began applauding exuberantly. One of the singers then walked over and turned Beethoven around to accept the audience’s acclaim. Even though he could not hear their clapping and cheers, he could see their five ovations, with handkerchiefs in the air, hats, and raised hands.

While the audience’s reception undoubtedly gratified Beethoven when he saw it, he was in a state of utter Joy directing his symphony before he ever turned around to see their response.

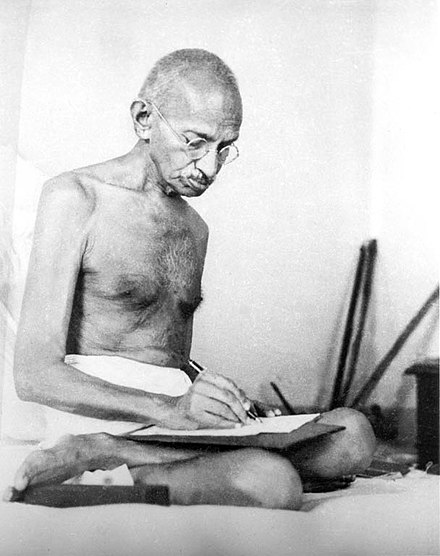

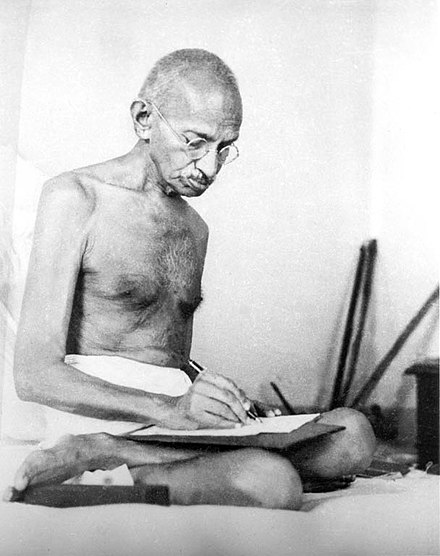

Mahatma Gandhi found an entirely different path to Joy. His life course led him from fear as a child and dismal failure as a young lawyer, to eventually leading the entire nation of India to freedom from the British Empire. To shrink the vastness of his 80-year life story into a few words, Gandhi came to realize that he did indeed have assets and abilities that he could access… but only when he stopped worrying about his own success or failure and instead put himself to work for the sake of others. Just as a trustee for a non-profit organization takes care to see that all the organization’s assets are put to the highest and best use, Gandhi came to see that his life did not belong to him, it belonged to the world.

With that realization, Gandhi cheerfully spent years locked in British-run prisons for his non-violent civil disobedience campaigns to free his people. He faced seemingly insurmountable obstacles and willingly looked death in the face on many occasions, knowing that his life was being spent for a greater cause than himself, following his dharma. Personal suffering became insignificant to him – it was all part of a deeper Joy.

Most people’s dharma lines are less grandiose – and absolutely as valuable – as those of Harriet Tubman, Beethoven and Gandhi. Yet the example of these three people’s lives begs the question of us: Are we open to finding and refinding our dharma, our life path, which could lead us – and others – to Deep Joy?

Dancing in Joy and resting in stillness with you,

Renée Tillotson

And you, dear reader?

Just hit reply – I always love hearing from you.

Get the Still & Moving App

This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)